We’re calling on you to join the #VoteforRivers campaign run by the Rivers Trust in the lead-up to the General Election on Thursday 4th July.

This is your chance to use the power we have as voters to advocate for nature restoration and to take this vital opportunity to speak up for healthy rivers.

We’ve set out asks under five headings, whether you plan to seek answers from candidates who come knocking on the door, question them at local hustings or want to write to them.

You can find the candidates running in your area using The Electoral Commission and download the letter to write to them, or have the asks handy when meeting candidates in person.

We want you to ask the new Government to:

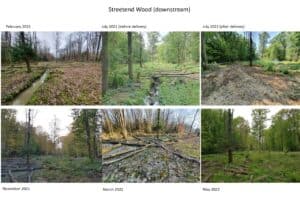

1. Prioritise nature recovery – make nature-based solutions like trees and wetlands to improve the environment and tackle climate change as first choice, rather than relying on chemicals and concrete.

For example, we at the South East Rivers Trust have just completed Chamber Mead wetlands in Ewell, Surrey, which diverts road runoff away from the River Hogsmill. Plants being established there will also bring huge biodiversity benefits to the Hogsmill Local Nature Reserve.

We are working on restoring water voles, eels and trout via our WET Hogsmill project, we have restored a section of the River Blackwater in Hampshire and the Wandle in Morden Hall Park with woody debris and by adding gravel.

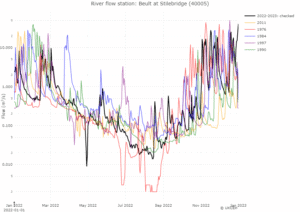

2. Improve our understanding of rivers – support better data and evidence to improve regulatory monitoring and recognise the value of citizen science alongside it.

Through our work engaging the public and encouraging them to take part in citizen science, we collect data on the health of our rivers.

Examples include training volunteers to:

- Discover how much misconnected plumbing is in our rivers through our Outfall Safari work

- Carry out riverfly monitoring to judge the health of rivers and whether there has been pollution, by finding invertebrates

- Survey where non-native invasive species are prevalent in our rivers

- Record detailed water quality testing results

3. Support education and engagement about rivers – No one will protect what they don’t know about or understand – and what they have not experienced. So we need the Government to support education about the environment and rivers at all levels.

The South East Rivers Trust has programmes supporting education of primary school children and community groups across London catchments and the River Mole.

Our events also demonstrate the value of our work through walks and talks across a wide range of topics and we take part in awareness campaigns such as London Rivers Week.

4. Make polluters pay – drive strong enforcement of those who pollute to turn the tide on the abuse of our rivers.

We have recently supported a campaign to clear Hoad’s Wood in Ashford of fly-tipping. After a petition, the Government has now issued a clean-up edict which will cost the taxpayer huge sums. Nobody has yet been traced to pay for the clean-up.

We work on various projects funded after pollution incidents, through mechanisms such as voluntary reparations. One is the Mending the Upper Mole project which allows us to expand awareness of rivers and carry out restoration in many ways far wider than the original incident.

5. Manage land with water in mind – empower collaborative working that gets everyone involved in restoring our rivers.

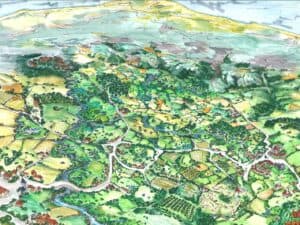

- At the South East Rivers Trust we lead several catchment partnerships across 12 river catchments. These work collaboratively with many other organisations and individuals to bring rivers back to life. They need investment and funding to do so.

- Our Holistic Water for Horticulture project also works with food growers in Kent and the South East to ensure water efficiency and resilience in the process of getting food from farm to fork.

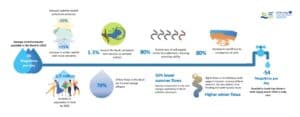

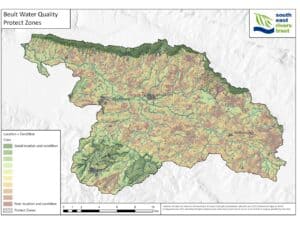

- This is part of the work of our Water and Land Stewardship team, which has worked closely with farmers on the River Beult in Kent on nature-based solutions to retain water and enhance biodiversity, for the benefit of wildlife and people. We are involved in national pilots for Environmental Land Management Schemes, funded by Government, working with farms to manage land in sustainable ways.

- For example, we are working with farmers and landowners and other environment NGOs on the River Darent catchment to implement a radical, large-scale approach to delivering climate benefits – starting with rivers.

Here are some questions you can ask your candidates

- How will you and your party tackle all types of pollution in our rivers? Sewage is not the only issue; farming and road runoff pollution are also devastating our rivers.

- Will your party boost funding for regulators and strengthen enforcement so polluters are made to pay for their pollution?

- How will your party work with nature to improve river health and tackle climate change?

- How will your party open up rivers and blue spaces in our towns and cities for health and wellbeing?

- How will your party support farmers and businesses manage their land sustainably for water?

No matter where you live across our 12 catchments, there is a river near you. Find our river using our map, using your postcode. There a hundreds of candidates standing for constituencies from Berkshire through Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex, Kent and south London who want your vote – so press them on the hot topics!

Thank you for standing up for rivers!

Sewage a campaign issue BBC London News, 28th May:

Use our email template:

If you are writing to your candidates, you could use or adapt the Rivers Trust’s template, by copying and pasting the information below or adding in your own asks on rivers. Don’t forget you can source candidate details via The Electoral Commission.

Dear [Candidate name],

I will be voting for rivers in the General Election on 4th July 2024 and, as a local resident and voter, need to know how you intend to stand up for our waterways.

The Rivers Trust’s State of Our Rivers Report 2024 lays bare the dire health of our waterways, which are facing devastating levels of pollution, swinging between extremes of flood and drought, and experiencing shocking drops in biodiversity:

0% of stretches of river in England are in good or high overall health.

This is not breaking news – the issues faced by our rivers have been hitting the headlines for years and causing widespread public outcry. Yet not enough is being done to restore or protect our waterways.

Healthy rivers should be a priority for the next Government. From re-wiggling rivers, restoring floodplains, and greening our urban spaces, restoring our rivers means securing community resilience, a future for wildlife, and action for climate.

This is why I am supporting The Rivers Trust’s asks for political candidates and parties:

Prioritise nature recovery – make nature-based solutions like trees and wetlands to improve the environment and tackle climate change first choice, rather than relying on chemicals and concrete.

Improve our understanding of rivers – support better data and evidence to improve regulatory monitoring and recognise the value of citizen science alongside it.

Support education about rivers – no one will understand or care about what they haven’t experienced. Outdoor learning is key to nurturing a lifelong love of rivers.

Make polluters pay – drive strong enforcement of those who pollute to turn the tide on the abuse of our rivers.

Manage land with water in mind – empower collaborative working that gets everyone involved in restoring our rivers.

Please let me know what actions you and your party intend to take to deliver the asks above and restore the health of our waterways.

I look forward to hearing from you and, if possible, please copy info@theriverstrust.org in your reply.

Yours sincerely,

[Sender name]